Queen pheromones

A worker tends to a Lasius niger queen, who is about to take off in search of a new colony. Photo: Stuart Hogton.

A worker tends to a Lasius niger queen, who is about to take off in search of a new colony. Photo: Stuart Hogton.

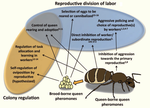

Queen pheromones are chemical signals produced by reproductive females, or queens, in social insects such as bees, ants, wasps, and termites. I am especially interested in queen pheromones that cause other colony members to become sterile, because reproductive division of labour is the defining – and most evolutionarily striking – characteristic of the social insects.

I have been working on queen pheromones since 2008, when I conducted the first experimental bioassay to identify a queen pheromone from an ant (the black garden ant, Lasius niger). In a series of follow-up papers, we showed that the queen pheromone signals the fecundity and condition and of the queen, suggesting that it is an ‘honest signal’ of the queen’s value to the workers. That is, the workers probably ‘choose’ to remain sterile when they perceive the presence of a healthy queen, since it is more profitable for them to reproduce indirectly by helping to raise the queen’s young (who are usually the workers' brothers and sisters).

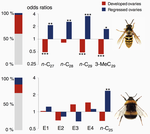

Later on, I co-discovered the first queen pheromone for a bumblebee and a wasp, in collaboration with Tom Wenseleers and colleagues. The queen pheromones of most ants, wasps and bees are quite similar, which is surprising given that these three groups evolved their eusocial societies independently, and have been evolving independently for well over 100 million years. This suggests that queen pheromones evolved from some sort of chemical signal (such as a sex pheromone signaling egg production) that was already present in the solitary insects that were the common ancestors of the eusocial Hymenoptera.

My most recent work focuses on the transcriptomic effects of queen pheromones. As one might expect of a pheromone that profoundly alters the behaviour and physiology of workers exposed to it, we find that queen pheromones affect the expression of a great many genes. We found striking similarity in the genetic circuits targetted by queen pheromones in bees and ants, which are separated by 150 million years of independent evolution.